Paul Smith believes in honesty, even when it’s uncomfortable. “I once had a girlfriend I’d split up with. Then the band went off to be on the TV and release records and whatnot. She phoned me up one day out of the blue a year later or so, and said, ‘My friends are talking, saying all these songs are about me, and I think it’s terrible.’ And I said – it was kind of a long conversation – ‘I just have to say: none of these songs are about you.’ She then felt bad about that, thinking, ‘Well, who are they about?!’”

That was the only time Paul’s highly personal lyrics for Maxïmo Park caused him any trouble with women. This seems hard to believe, but I dare not doubt his honesty. I commend the women he has been involved with since then for being extremely secure. You would need to be to deal with your partner telling tales like Drinking Martinis, I Haven’t Seen Her In Ages, or Hips And Lips. Unless you were entirely sure they were or weren’t about you. Paul’s honesty is one of the most intriguing aspects of Maxïmo Park’s music. His “overshares,” as some critics consider them, are the partial inspiration for their latest album’s title: Too Much Information.

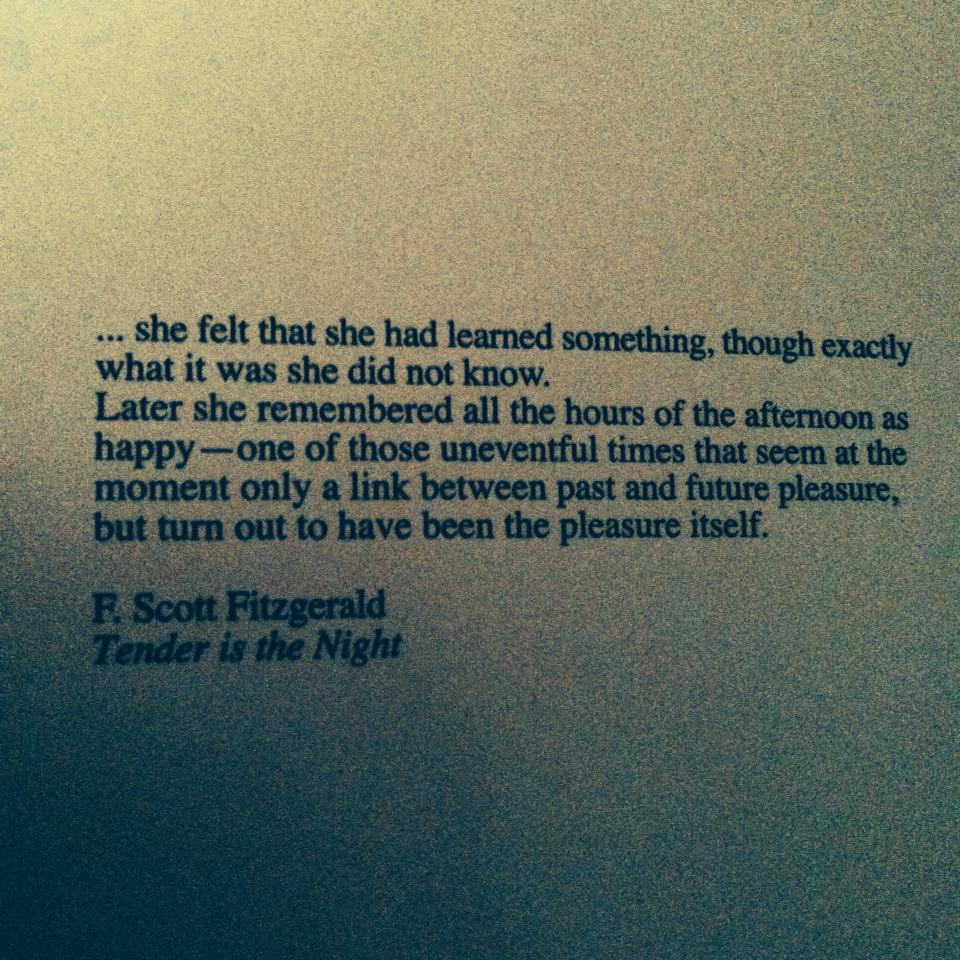

His girlfriends have probably been privy to his writing process relying more on the past than the present. “The songs are about small moments, really,” Paul explains. “You try to elevate them and make them into big things. It reminds me of a Fitzgerald quote that I put in the second album about how the moments that you remember, you don’t think about them at the time. They just pass, and they’re just another moment. But then you go back to that point and think, ‘Oh, that was the big deal. That moment was a beautiful one.’ I try to commemorate those moments if possible.” Maxïmo Park’s albums could be seen as scrapbooks of Paul’s life, captioned with universal truths.

He introduces Drinking Martinis to the Troubadour as “the most romantic song on our new album.” The song connects two nights with the same woman: one at a bar called Tokyo in Newcastle and another at the Hotel Kyoto. “There’s a kind of symmetry in the song which is, I suppose, traditional songwriting,” he says. While this symmetry is beautiful, the most striking lines come via his reflection: “We act as if the people we were are gone, but echoes remain. We act as if the way that we were was wrong, as if people change.” In these lines, Paul captures the universal truth that we are products of our past: all the moments, experiences, and behaviours that we may or may not approve of now. As much as we might change as people, the past makes us who we are. No matter how much we renounce our past, it is a part of us. It is Paul’s aim for his lyrics to resonate with everyone.

These epiphanies come to him while reflecting. “You think, ‘Ah, maybe nobody else has said it like this.’ Even though, I’m sure many people have experienced this same emotion or this same kind of moment.” As confident as he is that these important moments are a universal aspect of the human experience, he acknowledges that they may not be the same for everyone. He asks at the end of the song: “Now that you’re gone, do you feel anything?” Are these two evenings as important in the woman’s memory as they are in his? Do they make her feel anything? Wondering how much moments weigh on others’ memories or how they have experienced events differently to himself is a new theme for Paul on TMI. He used to stay in his own mind. In Lydia, the Ink Will Never Dry, he admits, “I don’t know about you, but it feels good to me.” Even of songs such as Where We’re Going, which clearly establishes that his partner does in fact know where they are going, he says, “It is just a confused song. It’s about somebody else who can guide you along in life. Even though maybe… if you both feel the same way, neither of you know exactly what you’re doing. But you provide the other person with a little bit of strength.” This new approach to memory is just one way that Maxïmo Park push themselves further on their latest album.

Paul says new developments in their music come from internal pressure. For Paul, it is simply a pressure to live up to what they have done previously. He is proud of everything that Maxïmo Park have done. The task they set for themselves each album is to do something different but of the same quality. Record companies or managers can urge a band to go a certain direction (or simply hurry up because the money is running out), but bands must stay true to their artistic vision. The band recorded TMI entirely themselves. “I’ve said a number of times that I wanted us to have more electronic influences on the records,” he says. “We were tiptoeing our way, bit by bit, album by album. And that’s great because that is our evolution. That is our progress.” The electronic songs on the album, like Brain Cells and Leave This Island, allow a new, more subtle sound for their music. Paul believes the electronic element preserves the boldness and edge associated with Maxïmo Park. They would not want themselves to become unrecognisable to the people who like their band just for the sake of artistic expression. That’s why side projects exist.

“Music for me is just a continuum,” Paul explains. “‘What’s next? Okay, let’s do this with the band; let’s do that by myself; let’s do that with my other friend.’ It’s just a natural, logical thing , whereas I think you can get kind of bogged down in the career aspect of it. I think that’s where a lot of bands fail. They’ve tried to keep up with something that’s an illusion. Fashion is this kind of illusory mirage. It’s there, and then it’s not. If you try and do your own thing away from fashions and choose your own way of being, then that will serve you well in the end because you only have yourself to answer to. That takes the pressure off in a way because the pressure is all internal.” He pauses. “I think it’s a confident record. Maybe that’s what I’m trying to say.”

The band built their own studio in Newcastle. Aside from the cost probably being less than building a studio in London, it fits that they would choose to put their studio in the city where the band was formed. Unlike most bands who eventually lose their roots, their music remains infused with northeast flavours. Much of Paul’s lyrics feature allusions to the city. The monument of By the Monument is a common place to meet friends in the city centre. The “revolving dance floor in the middle of the river” of In Another World (You Would’ve Found Yourself By Now) was located on the River Tyne. And of course Tokyo and the river in Drinking Martinis. (But listener beware assumptions: the band’s most commercially successful single, Books From Boxes, actually takes place in London.) Then there is Paul’s northeastern accent.

At the time Maxïmo Park were getting attention from the music press, bands were popping up from all over Britain with frontmen armed with regional accents. (NME very recently gave credit to The Futureheads’ first album in 2004.) Even pop artists such as Lily Allen embraced the trend. There were many people hoping it would not be a trend at all, but the new rule for British music. “I thought we’d got rid of [Brits singing in American accents] and perhaps it had changed,” says Paul. A decade on, it seems the only artists left singing in British accents are those who were doing it ten years ago. He sees a disconnect between singing in a false accent and providing an honest message for the listener. “If people are saying that they’re expressing themselves and not even singing in their own voice – pretending to be somebody else while supposedly giving people something real – I find that a bit offensive.” He cannot imagine ever switching to an American singing voice. Music is about self-expression and he best expresses himself in his own voice.

Honesty is not only what you say: it’s how you say it.